Citation for William Binchy, Doctor of Celtic Literature honoris causa, April 1973

Item

Title

Citation for William Binchy, Doctor of Celtic Literature honoris causa, April 1973

Format

Text

Identifier

VHD0008

Description

Text of the citation read by Professor Michael Duignan, NUI Galway, on the occasion of the conferring of an honorary doctorate on Professor William Binchy, 12 April 1973.

Language

English

Latin

German

Contributor

Transcription

TEXT OF INTRODUCTORY ADDRESS DELIVERED BY PROFESSOR MICHAEL V. DUIGNAN, M.A., April 12th, 1973, on the occasion of the conferring of the degree of Doctor of Celtic Literature, honoris causa, on Professor Daniel A. Binchy, M.A., DR. PHIL., D.LITT., D. ès L., Barrister-at-Law.

CHANCELLOR, AND MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY:

Today I have the rare, if not the unique, honour of presenting to you for the honorary degree of Doctor of Celtic Literature a scholar who, more than forty years ago, was, at one and the same time, one of my professors and one of my classmates in University College, Dublin.

Daniel A. Binchy was born in Charleville, County Cork, of a merchant family whose younger sons traditionally betook themselves to the legal profession. It was, therefore, preordained that, when he entered University College, Dublin, from Clongowes Wood College, where the core of his education had been the Ancient Classics, his university studies should be directed towards a lawyer's career. In 1919 he was awarded the B.A. degree, with First Class Honours, in Legal and Political Science and, the following year, the M.A. degree in Modern Irish History, again with First Class Honours.

From University College, Dublin, he proceeded to the University of Munich, returning briefly to Dublin in 1921 to be called to the Bar. In 1924 he was awarded the Munich Doctorate in Philosophy, the subject of his dissertation being the history of the Schottenkloester, that celebrated Irish Benedictine Congregation of South Germany and Austria, whose mother house was the Abbey of St. James the Greater and St. Gertrude at Regensburg, but which was not without its Cork affiliations. In the years 1924 to 1926 he studied at the Ecole des Chartes, Paris, having already (1924) been appointed Professor of Roman Law and Jurisprudence in University College, Dublin. His interest in historical jurisprudence very soon aroused in him a lively curiosity about the ancient laws of Ireland, at that time, not only most inadequately published, but also largely neglected, the only active workers on them being Professor Eoin Mac Neill of University College, Dublin, Geheimrat Thurneysen of Bonn, and Charles Plummer of Oxford. In 1926, and notwithstanding the fact that he had, that same year, shouldered the burden of acting as substitute for his colleague, the Professor of History, Dr. Binchy, with characteristic energy and thoroughness, set about equipping himself for Irish legal studies by joining Professor Osborn Bergin's Old Irish lectures for beginners, and by making the first of a series of long visits to Dunquin so as to master the living Irish language.

The first outward sign of the fresh impetus which Dr. Binchy gave to the study of the early Irish law tracts was a noteworthy seminar, on the legal status of women in Gaelic society, which was conducted by Thurneysen in Dublin in the first half of 1929. Later that year came the first major interruption in Dr. Binchy's own researches: he was called on by the Government to serve as first Irish Minister Plenipotentiary to Germany. After three years, he resigned his post in order to resume his professorship and his researches, seizing the opportunity to spend some months attending Thurneysen's postgraduate class in Bonn. The following year the title of his chair was changed to that of the Professorship of Roman Law, Jurisprudence, and Legal History (including Ancient Irish Law).

The first major fruit of his return to the Grove of Akademe was the publication (1936) of Studies in Early Irish Law, the proceedings of Thurneysen's 1929, Dublin seminar edited by Professor Myles Dillon and Professor Binchy, and to which Professor Binchy himself made two important contributions.

In the middle of the later thirties Dr Binchy’s home was the weekly meeting place of a group of distinguished scholars including Myles Dillon, Michael Tierney, Gerard Murphy—so admired and loved by all—and Monsignor Patrick Boylan. These Saturday gatherings —et ego in Arcadia—with their wide-ranging discussions of scholarly, literary, economic, political, and international questions, were unforgettable experiences for the neophytes so generously, and so hospitably, admitted to them. It was to one of these gatherings that Dr Binchy submitted, for criticism, the first draft of a project for a postgraduate School of Celtic Studies in Dublin, a project eventually accepted by you, Chancellor, as Head of the Government, and incorporated in your Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Before that had come to pass, however, Dr Binchy had felt constrained to interrupt his legal researches yet again, and to undertake, on behalf of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, the investigations which were to result in that noteworthy book, Church and State in Fascist Italy (1941). A third distraction quickly followed, when Dr. Binchy joined with Professor Osborn Bergin in preparing the English translation of Thurneysen's celebrated A Grammar of Old Irish (1946 and 1949).

In 1945 Professor Binchy was Rhys Memorial Lecturer to the British Academy.

In 1945 also he was elected to a Senior Research Fellowship in Corpus Christi College, Oxford, where, by happy chance, he was assigned the rooms which had been those of Charles Plummer. The cloistered quiet of Corpus Christi College might have been expected to distract Dr. Binchy from the harsh realities of the world about him. Instead, his ever continuing concern for the problems of everyday life impelled him to deliver at Oxford some striking lectures on the decay of the Natural Law in parliamentary societies.

In 1948 Dr Binchy resigned his University professorship to accept a Professorship in the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Promoted to the rank of Senior Professor in 1950, he resigned from his Oxford Fellowship. In 1952, he was Lowell Lecturer in Boston; in 1954, Visiting Professor of Celtic in Harvard University; in 1962 & 1963, Gregynog Lecturer in the University of Wales; in 1966, O'Donnell Lecturer to the University of Oxford. To these international distinctions were added many others: an honorary doctorate fron the University of Dublin in 1956; in 1963 one from the University of Wales; in 1971 one from the University of Haute Bretagne (Rennes); in 1972 an Honorary Fellowship in Corpus Christi College, Oxford; in 1973 an honorary doctorate from the Queen's University of Belfast; and today, our own University enrolls among its honorary graduates one of its most distinguished sons.

In addition to two books, Professor Binchy has published more than thirty papers on historical, linguistic, and juristic subjects, not to mention his papers on political problems at home and abroad. And his magnum opus, his Meisterwerk, is in the press: Corpus Iuris Hibernici, a complete diplomatic edition of all the known early Irish law tracts. It is on this he has spent so large a part of so active a life. It is for this, I feel sure, he would wish best to be remembered. If he is anything, he is surely a scholar qui iuris nodos et legum aenigmata solvit, a man such as Terence had in mind when he said nil tam difficilest quin quaerendo investigari possit. And, despite the weight of his scholarship, and of the honours heaped upon him, despite his standards of academic and personal integrity, he has always remained a man of gaiety and of generosity, particularly towards younger scholars. Of him one can say with truth that he has 'neither the scholar's melancholy nor the lawyer's', for he has ever been a lover of the arts, of poetry, and of music; likewise a lover of the chase-perhaps not exactly 'a mighty hunter before the Lord', but certainly a worthy Nimrod variation.

Chancellor, I resist the temptation to conclude by seeing in Professor Binchy that abysme de science which Gargantua wished to see in Pantagruel, not for fear of offending so eminent a scholar, but rather because I believe he would prefer the simplicity and directness of another distinguished Corkman, a dear friend, an ardent admirer, indeed, in his own brilliant way, a disciple. And so despite the fact that he has no cat, I end by applying to Dr. Binchy an adaptation of the closing lines of Frank O Connor rendering of a familiar early Irish poem:

‘He too, making dark things clear,

Is of his trade a master’.

CHANCELLOR, AND MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY:

Today I have the rare, if not the unique, honour of presenting to you for the honorary degree of Doctor of Celtic Literature a scholar who, more than forty years ago, was, at one and the same time, one of my professors and one of my classmates in University College, Dublin.

Daniel A. Binchy was born in Charleville, County Cork, of a merchant family whose younger sons traditionally betook themselves to the legal profession. It was, therefore, preordained that, when he entered University College, Dublin, from Clongowes Wood College, where the core of his education had been the Ancient Classics, his university studies should be directed towards a lawyer's career. In 1919 he was awarded the B.A. degree, with First Class Honours, in Legal and Political Science and, the following year, the M.A. degree in Modern Irish History, again with First Class Honours.

From University College, Dublin, he proceeded to the University of Munich, returning briefly to Dublin in 1921 to be called to the Bar. In 1924 he was awarded the Munich Doctorate in Philosophy, the subject of his dissertation being the history of the Schottenkloester, that celebrated Irish Benedictine Congregation of South Germany and Austria, whose mother house was the Abbey of St. James the Greater and St. Gertrude at Regensburg, but which was not without its Cork affiliations. In the years 1924 to 1926 he studied at the Ecole des Chartes, Paris, having already (1924) been appointed Professor of Roman Law and Jurisprudence in University College, Dublin. His interest in historical jurisprudence very soon aroused in him a lively curiosity about the ancient laws of Ireland, at that time, not only most inadequately published, but also largely neglected, the only active workers on them being Professor Eoin Mac Neill of University College, Dublin, Geheimrat Thurneysen of Bonn, and Charles Plummer of Oxford. In 1926, and notwithstanding the fact that he had, that same year, shouldered the burden of acting as substitute for his colleague, the Professor of History, Dr. Binchy, with characteristic energy and thoroughness, set about equipping himself for Irish legal studies by joining Professor Osborn Bergin's Old Irish lectures for beginners, and by making the first of a series of long visits to Dunquin so as to master the living Irish language.

The first outward sign of the fresh impetus which Dr. Binchy gave to the study of the early Irish law tracts was a noteworthy seminar, on the legal status of women in Gaelic society, which was conducted by Thurneysen in Dublin in the first half of 1929. Later that year came the first major interruption in Dr. Binchy's own researches: he was called on by the Government to serve as first Irish Minister Plenipotentiary to Germany. After three years, he resigned his post in order to resume his professorship and his researches, seizing the opportunity to spend some months attending Thurneysen's postgraduate class in Bonn. The following year the title of his chair was changed to that of the Professorship of Roman Law, Jurisprudence, and Legal History (including Ancient Irish Law).

The first major fruit of his return to the Grove of Akademe was the publication (1936) of Studies in Early Irish Law, the proceedings of Thurneysen's 1929, Dublin seminar edited by Professor Myles Dillon and Professor Binchy, and to which Professor Binchy himself made two important contributions.

In the middle of the later thirties Dr Binchy’s home was the weekly meeting place of a group of distinguished scholars including Myles Dillon, Michael Tierney, Gerard Murphy—so admired and loved by all—and Monsignor Patrick Boylan. These Saturday gatherings —et ego in Arcadia—with their wide-ranging discussions of scholarly, literary, economic, political, and international questions, were unforgettable experiences for the neophytes so generously, and so hospitably, admitted to them. It was to one of these gatherings that Dr Binchy submitted, for criticism, the first draft of a project for a postgraduate School of Celtic Studies in Dublin, a project eventually accepted by you, Chancellor, as Head of the Government, and incorporated in your Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Before that had come to pass, however, Dr Binchy had felt constrained to interrupt his legal researches yet again, and to undertake, on behalf of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, the investigations which were to result in that noteworthy book, Church and State in Fascist Italy (1941). A third distraction quickly followed, when Dr. Binchy joined with Professor Osborn Bergin in preparing the English translation of Thurneysen's celebrated A Grammar of Old Irish (1946 and 1949).

In 1945 Professor Binchy was Rhys Memorial Lecturer to the British Academy.

In 1945 also he was elected to a Senior Research Fellowship in Corpus Christi College, Oxford, where, by happy chance, he was assigned the rooms which had been those of Charles Plummer. The cloistered quiet of Corpus Christi College might have been expected to distract Dr. Binchy from the harsh realities of the world about him. Instead, his ever continuing concern for the problems of everyday life impelled him to deliver at Oxford some striking lectures on the decay of the Natural Law in parliamentary societies.

In 1948 Dr Binchy resigned his University professorship to accept a Professorship in the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. Promoted to the rank of Senior Professor in 1950, he resigned from his Oxford Fellowship. In 1952, he was Lowell Lecturer in Boston; in 1954, Visiting Professor of Celtic in Harvard University; in 1962 & 1963, Gregynog Lecturer in the University of Wales; in 1966, O'Donnell Lecturer to the University of Oxford. To these international distinctions were added many others: an honorary doctorate fron the University of Dublin in 1956; in 1963 one from the University of Wales; in 1971 one from the University of Haute Bretagne (Rennes); in 1972 an Honorary Fellowship in Corpus Christi College, Oxford; in 1973 an honorary doctorate from the Queen's University of Belfast; and today, our own University enrolls among its honorary graduates one of its most distinguished sons.

In addition to two books, Professor Binchy has published more than thirty papers on historical, linguistic, and juristic subjects, not to mention his papers on political problems at home and abroad. And his magnum opus, his Meisterwerk, is in the press: Corpus Iuris Hibernici, a complete diplomatic edition of all the known early Irish law tracts. It is on this he has spent so large a part of so active a life. It is for this, I feel sure, he would wish best to be remembered. If he is anything, he is surely a scholar qui iuris nodos et legum aenigmata solvit, a man such as Terence had in mind when he said nil tam difficilest quin quaerendo investigari possit. And, despite the weight of his scholarship, and of the honours heaped upon him, despite his standards of academic and personal integrity, he has always remained a man of gaiety and of generosity, particularly towards younger scholars. Of him one can say with truth that he has 'neither the scholar's melancholy nor the lawyer's', for he has ever been a lover of the arts, of poetry, and of music; likewise a lover of the chase-perhaps not exactly 'a mighty hunter before the Lord', but certainly a worthy Nimrod variation.

Chancellor, I resist the temptation to conclude by seeing in Professor Binchy that abysme de science which Gargantua wished to see in Pantagruel, not for fear of offending so eminent a scholar, but rather because I believe he would prefer the simplicity and directness of another distinguished Corkman, a dear friend, an ardent admirer, indeed, in his own brilliant way, a disciple. And so despite the fact that he has no cat, I end by applying to Dr. Binchy an adaptation of the closing lines of Frank O Connor rendering of a familiar early Irish poem:

‘He too, making dark things clear,

Is of his trade a master’.

Rights

This text may be used for non-commercial purposes under CC BY-NC-SA see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Linked resources

Filter by property

| Title | Alternate label | Class |

|---|---|---|

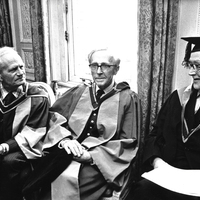

W. Hayes, D. Binchy and M. Duignan, 1973 W. Hayes, D. Binchy and M. Duignan, 1973 |

Image |