Brian Friel: Place and the Playwright

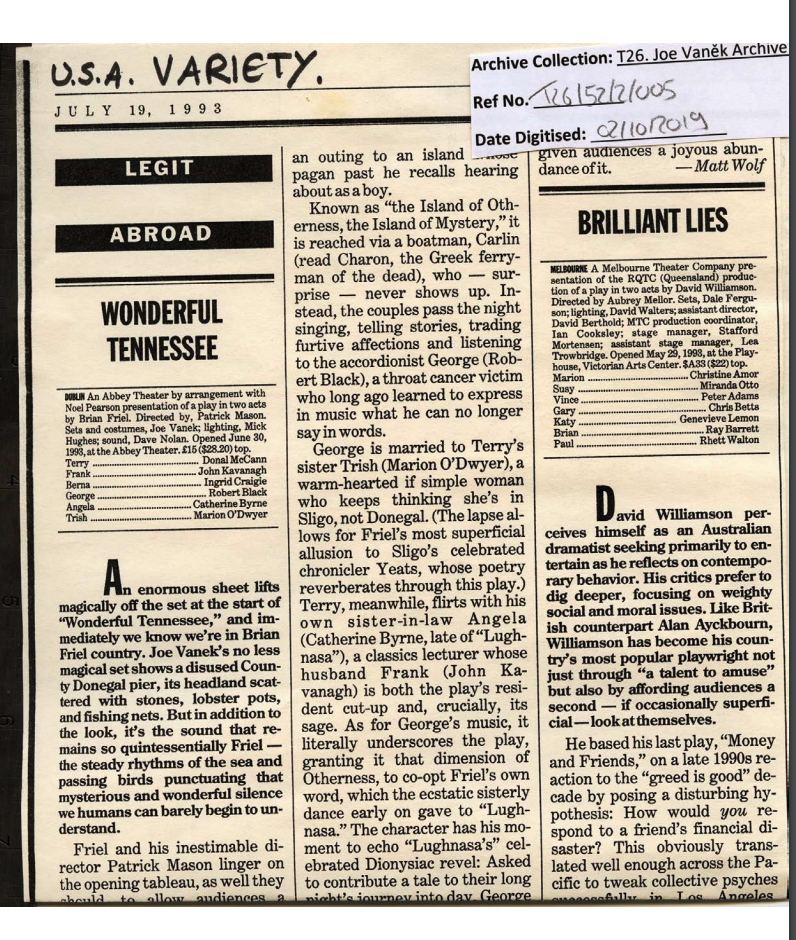

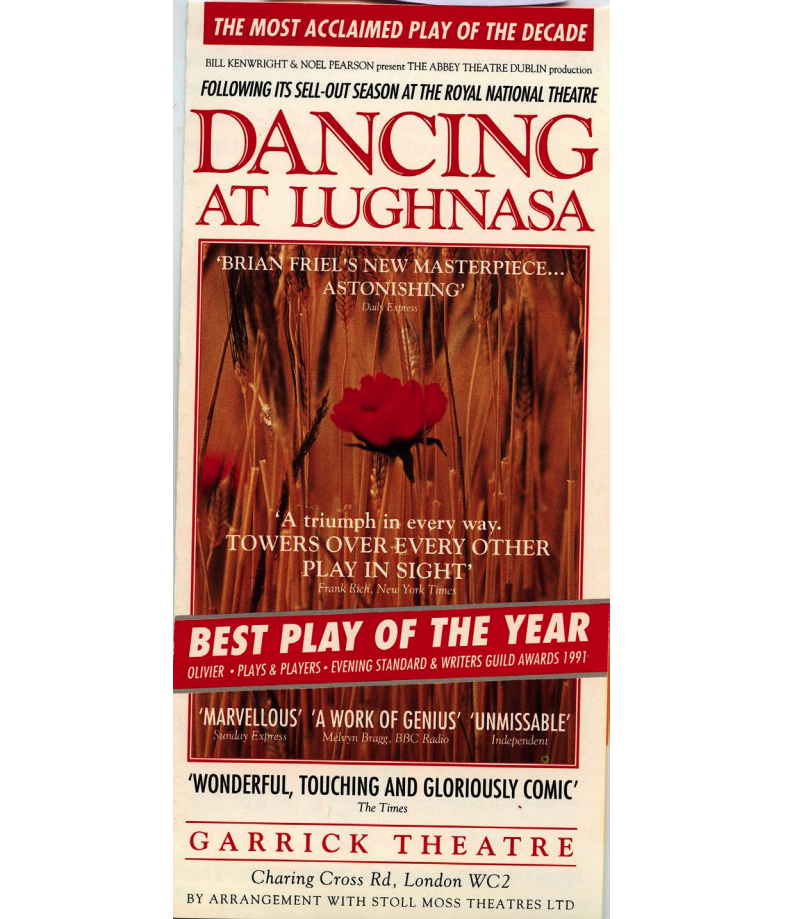

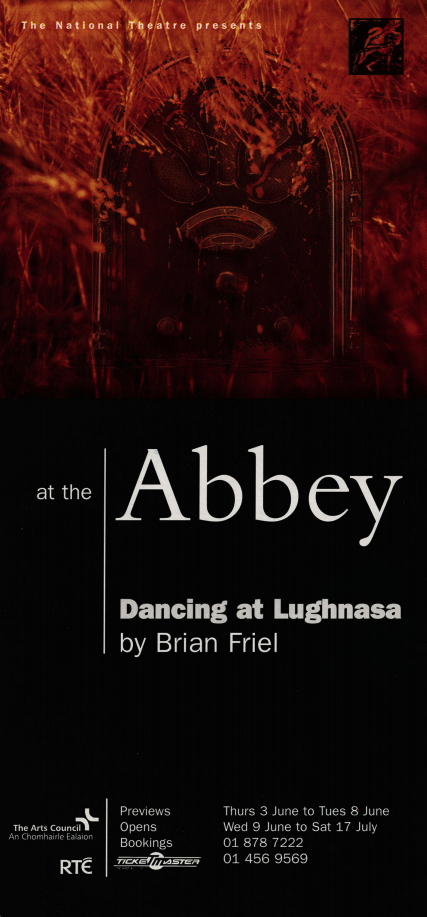

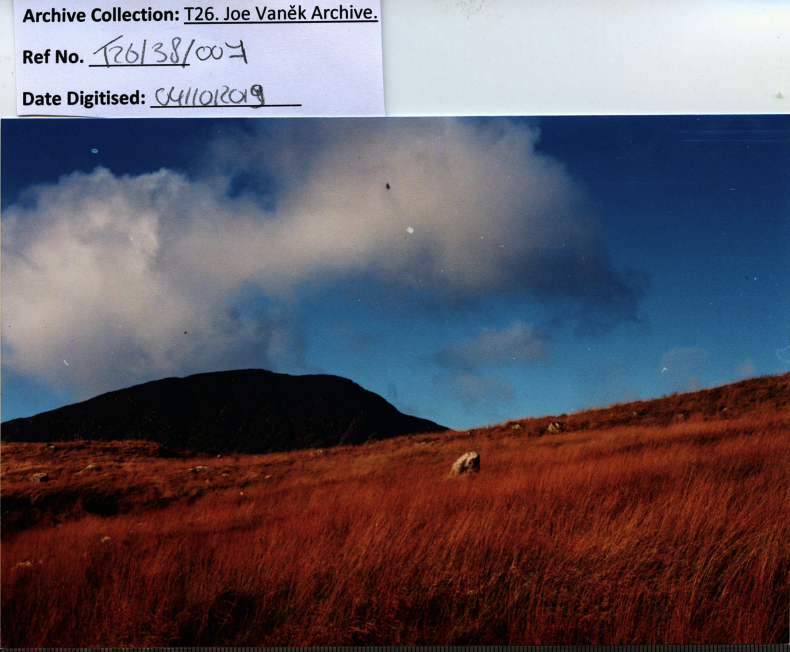

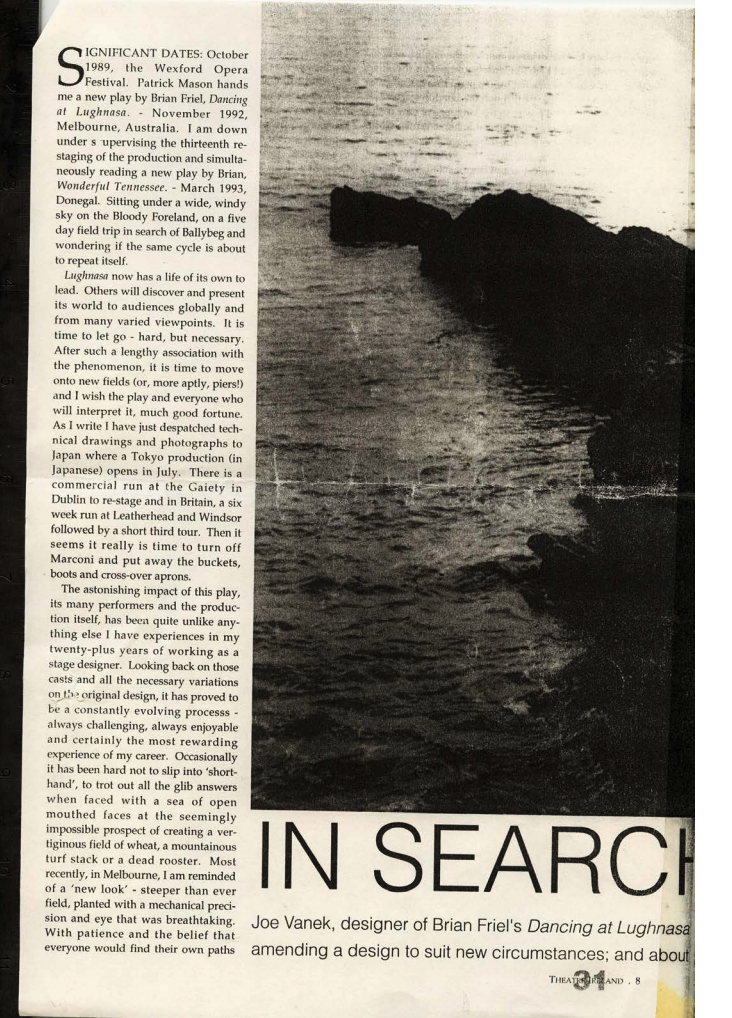

Dancing at Lughnasa (1990) is the oldest collaboration between Friel and Vaněk showcased in this archive, and it is arguably Vaněk’s most well-known design, earning him two Tony award nominations. The archive contains an article that details Vaněk’s journey through Donegal, which was the primary inspiration for Friel’s fictional Ballybeg, and a selection of photographs that where taken during his research. This includes an image of a hill covered in glowing wheat, which became the defining image of Dancing at Lughnasa and was incorporated in all subsequent productions, both nationally and internationally, under Vaněk’s care: “You needed the reality of the kitchen but you didn’t need to see the four walls, the world that went beyond that was a symbolic world. The cornfield was a metaphor for pagan summer.” The archive includes an interview with Vaněk in which he explains the difficulty of reinventing this design for different theatres while maintaining its essence. This essence may be described as the play’s nostalgic look at Ireland or, as Vaněk puts it, seeing Ireland “through a sepia tint.” It follows Michael (Gerard McSorley) as he fondly recounts his childhood in a Ballybeg cottage with his mother and her four sisters. The lovely memories are increasingly coloured, however, by the threat that their way of life will soon be destroyed. The play’s focus on memory and nostalgia is characteristic of Friel’s writing. Dancing at Lughnasa is, moreover, one of the first times that Vaněk collaborated with director Patrick Mason. Vaněk and Mason have worked together frequently since and they have produced, among other things, two more plays by Friel: Wonderful Tennessee (1993) and Performances (2003).

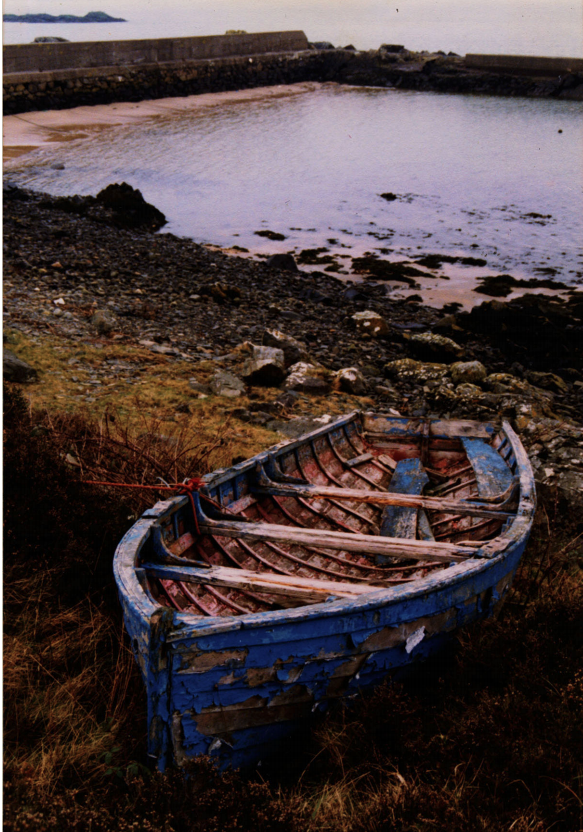

Like Dancing at Lughnasa, Wonderful Tennessee (1993) is set in the fictional Ballybeg. Vaněk once again travelled to Donegal to find inspiration for his designs. The archive includes an article detailing this process and one of the photographs that Vaněk took during his research, which showcases the plays connection to piers and waterfronts. In Wonderful Tennessee, Terry (Donal McCann) invites two couples to join his wife (Ingrid Craigie) and him on a trip to “the Island of Otherness, the Island of Mystery.” The boat, however, never shows up and they spent the night sharing stories and listening to George (Robert Black) play the accordion. As a throat cancer survivor, George is forced to rely on music to convey what he can no longer say out loud. The craft of storytelling, both through spoken narrative and music, is at the core of the production. As such, the dialogue is rich with symbolism and literary allusions. This surreal atmosphere is enhanced by Vaněk’s ‘floating’ set design, placing Wonderful Tennessee with one foot in the mythological world and with the other in Donegal.

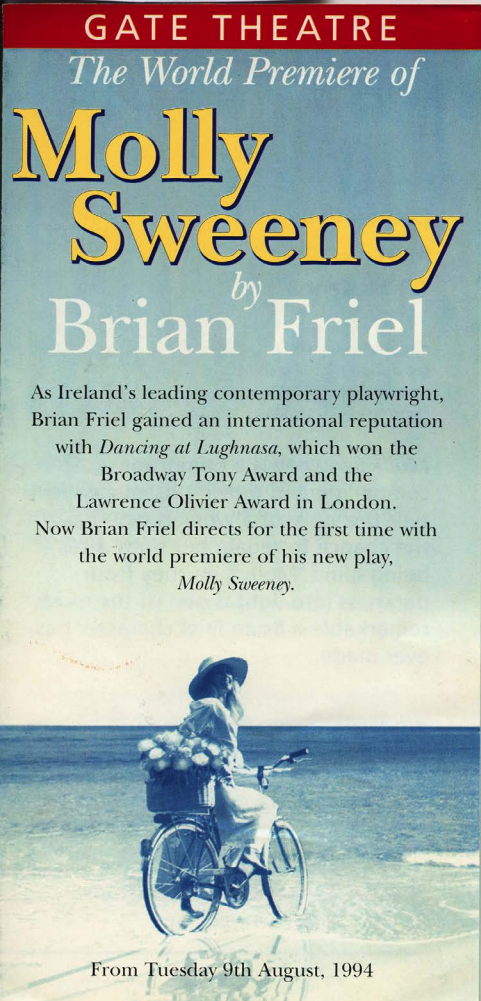

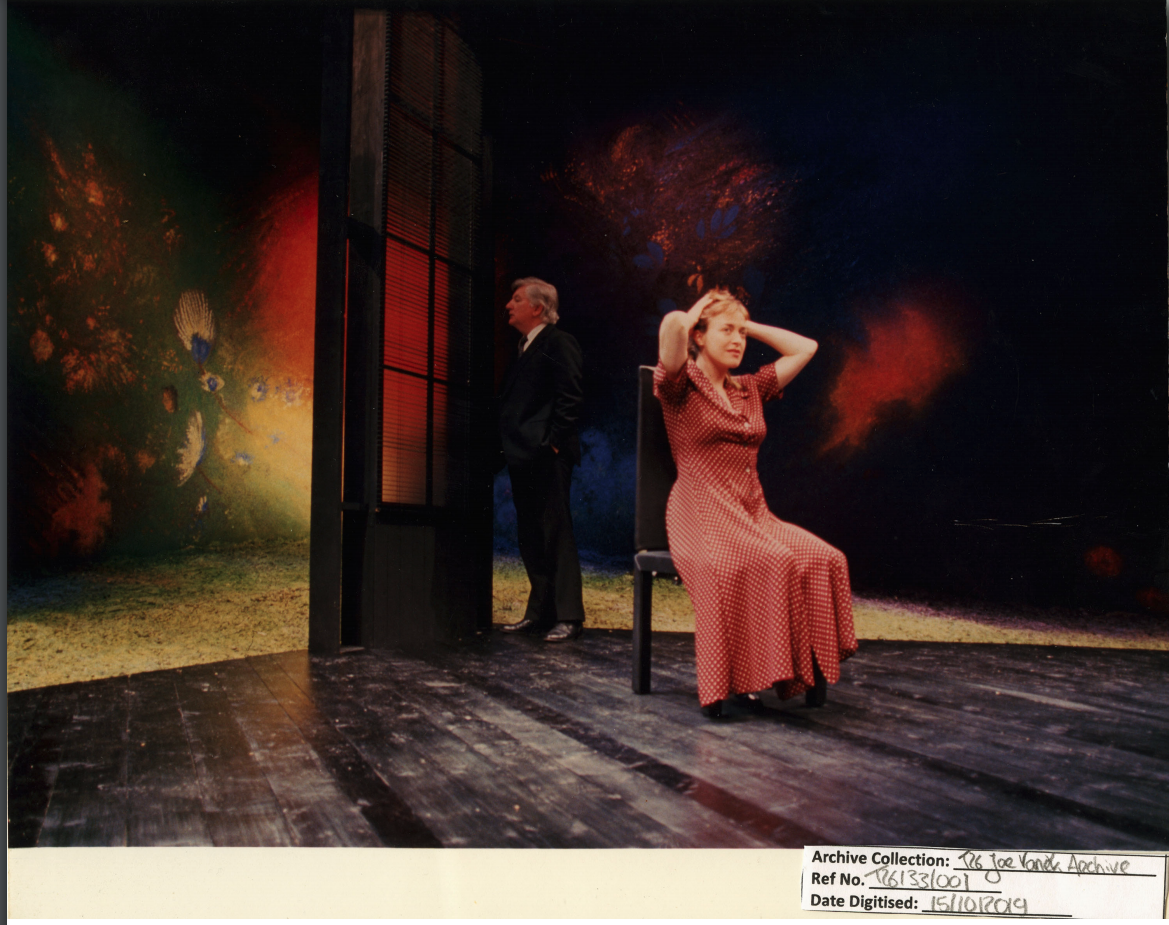

Molly Sweeney (1994) is also, in many ways, an exercise in storytelling. The play weaves together the perspectives of Molly Sweeney (Dawn Bradfield), her husband (Peter Hanly), and the ophthalmologist (Michael Byrne), who succeeds in restoring Molly’s sight. Rather than healing, the experience is frightening to Molly, who is confronted with ‘seeing’ but not understanding a reality that is so far removed from what she imagined. As a result, she retreats further and further into her own fantasies. Vaněk’s waiting room set seems to reflect this; rather than using clinical white, the walls are splattered in bright colours and fantastical floral designs.

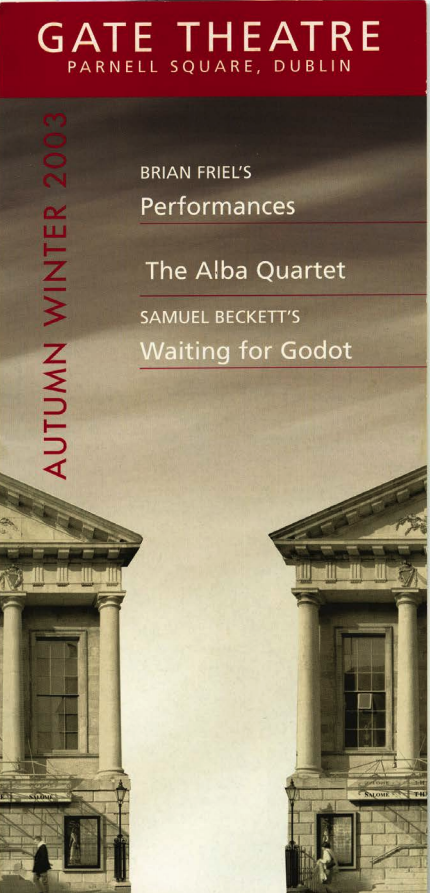

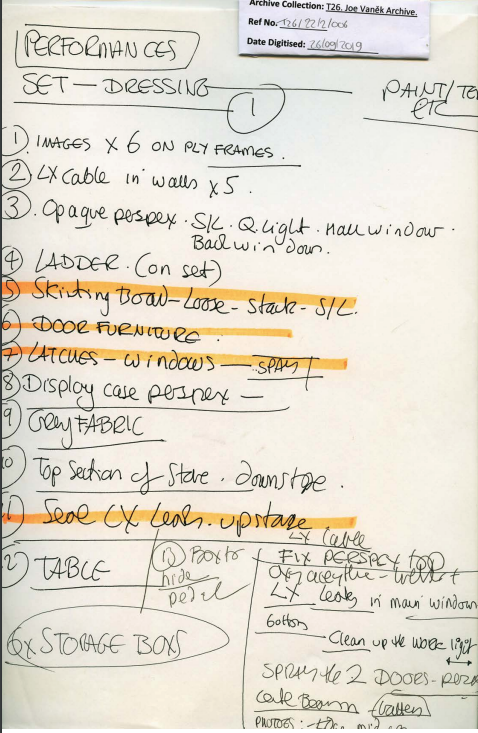

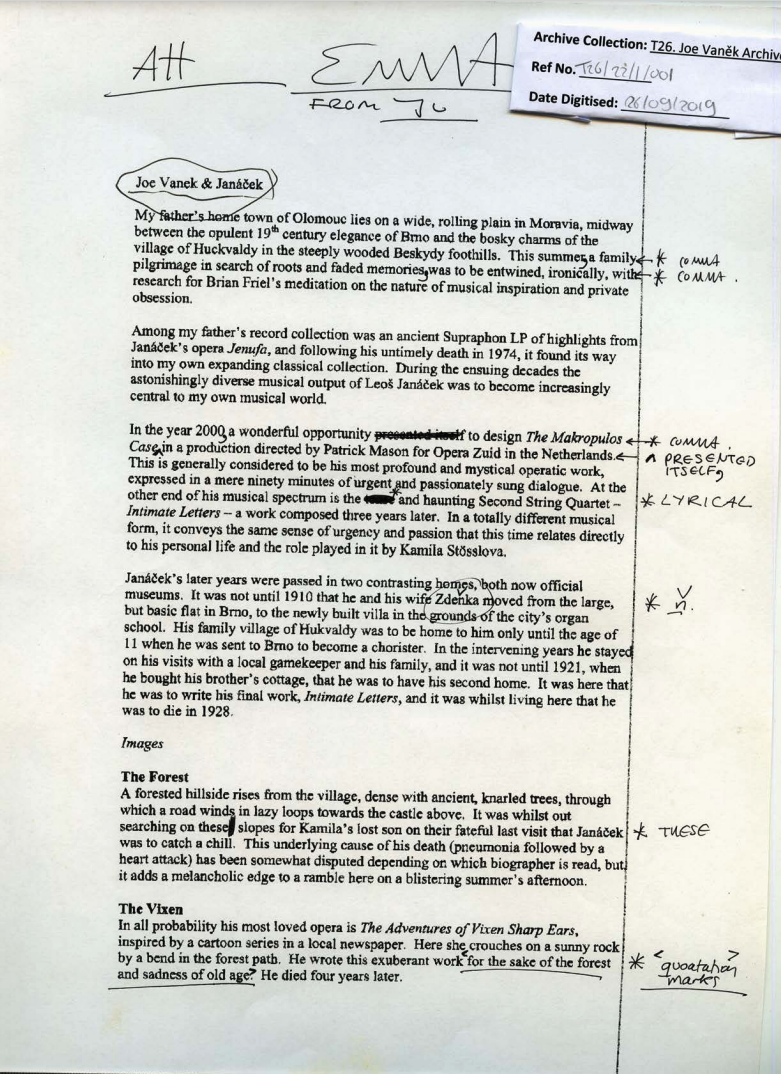

Friel’s Performances (2003) shows an interview between eager Ph.D. student, Anezka Ungrova (Niamh Linehan) and deceased, Czech composer Leos Janacek (Ion Caramitru), who is the subject of her thesis. Their meeting is set somewhere between reality and fantasy, and is alternatively interrupted and accompanied by Janacek’s symphonies, performed by the Second String Quarter (the Alba String Quartet). Vaněk’s stage design conveys and heightens this surreal setting by drawing inspiration from Janacek’s home-turned-museum in Prague. The archive contains photographs from Vaněk’s visit to this museum and the particular pieces he chose as vocal points for his stage design (e.g. the statue of a fox, a lyre, and more). In this surreal lieu de memoire, Friel’s Janacek finds himself forced to defend his legacy to Ungrova, who maintains that Janacek’s work was inspired by his affair with a married woman. The play deals with memory, legacy and the creation of art; themes that have been at the centre of Friel’s oeuvre.

In contrast to the previous productions, Vaněk’s design for Aristocrats (2003) had a more realistic approach and displayed great attention to the play’s historical context. The play is set in the fictional Ballybeg Hall, a Gregorian mansion or ‘big house’ in County Donegal, that belongs to the O’Donnell family. Ben Barnes, the director of this production, notes how Vaněk’s dilapidated set perfectly mirrors the state of the family and the lifestyle they represent: “The garden and facade of the house where the action takes place, with its buried croquet lawn, crumbling masonry, dampness above the picture rails and peeling wallpaper below them, its shabby furniture which has seen better days and the lead-less roof vulnerable to the elements became the perfect metaphor for a world teetering on the brink of collapse and already consigned to the past by the ‘clash of useless swords’ everywhere audible in the terrible decade of 1970s Ireland.” The archive includes photographs of the intricate set that showcases both the inside and outside of the decaying building.

A Month in the Country (2006) is Friel’s translation and adaptation of Ivan Turgenev’s play of the same name. The play centres around a rich landowner’s wife, Natalya (Derbhle Crotty) whose only source of entertainment is the affection of her admirer Rakitan (Declan Conlon). This changes when a young student, Aleksey (Laurence Kinlan), is hired to tutor Natalya’s son. She falls in love with him, but so does her young ward Vera (Elaine Symons). The play then follows the different misunderstandings that arise as all four characters try to win the affection of their loved one. Joe Vaněk’s design for Jason Byrne’s production includes tall, sheer drapes that cover the entire backdrop, giving the set an airy illusion while also symbolising how sheltered Natalya and the other characters are from the rest of the world. Photographs of the set and costume design can be found in the archive.