Opposition to the War / I gCoinne an Chogaidh

Support for the war effort was widespread in Galway town; local republican, Thomas Courtney, recalled ‘it wasn’t a case of if you were going to join up, but when’.

Recruitment meetings were sometimes raucous affairs, however, and street fighting between small groups of Irish Volunteers, who argued against Irish participation in the war, and their more numerous rivals from the National Volunteers, was described by the Connacht Tribune in October 1914 as resembling ‘guerrilla warfare on a small scale’. At a recruitment rally in Eyre Square in July 1915, Máirtín Mór McDonogh, the town’s leading merchant, ridiculed a group of agricultural labourers waiting to be hired nearby: ‘I’ll hire you and I will give you more pay than you will get from the farmers. Why do ye not go? Perhaps ye were thinking that on the lands that ye were going to there would be no German bullets; well, ye will be in as much danger on the bogs from God’s lightning as on the battlefield from German bullets.’

Following John Redmond’s pledge to support the British war effort in September 1914, the University’s Volunteer company held a meeting behind closed doors and after voting to support John Redmond, refused to release the names of the new officers or the content of their debate to local newspapers. Republican opposition to the war in Galway remained small and ineffectual. Professors Ó Maille and MacÉnrí became increasingly associated with public criticism of the actions of John Redmond.

Following the clashes between Sinn Féin supporters and Irish Parliamentary Party members in October 1914, Thomas Kenny, editor of the influential Connacht Tribune wrote, ‘Sinn Féin has been treated with generous tolerance in the city, it has grossly abused that tolerance… now the attitude is that tolerance has reached its limit, the puny plotters have only themselves to blame.’

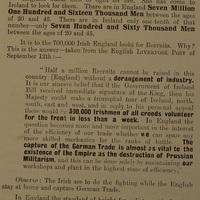

Thomas Hynes (1879-1966) worked as a laboratory attendant / technician at UCG for more than fifty years. A member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Irish Volunteers, he produced stink bombs in the College’s chemistry laboratory which were hurled on at least one occasion into a recruitment meeting: ‘We tried to break up recruitment meetings but we generally got beaten up ourselves as at least eighty per cent of the population was hostile to Sinn Féin, for a number of their husbands and sons were in the English army and navy.’

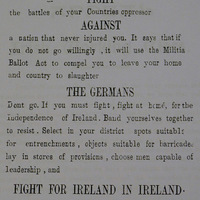

Following the release of stink bombs at a recruitment meeting in the Town Hall in October 1914, the Galway Express excoriated the ‘German Huns in Galway’, falsely alleging that sulphuric acid was used in the disruption:

A more infamously cowardly proceeding than that stated to have taken place has hardly been exceeded by the Huns in Belgium... The Huns are cultured, there is no claim to culture in Galway. Sulphuric acid is commonly thrown by jealous women who would blind and disfigure a rival in a love affair. For liberty loving men to squirt it at a platform of people exercising the common liberty of discussion is an example of the ‘liberty’ that ‘ourselves alone’ if left ‘alone’ would accord to free men.

I gCoinne an Chogaidh

Bhí tacaíocht don chogadh forleathan i mBaile na Gaillimhe. Dúirt an poblachtánach áitiúil, Thomas Courtney, ‘it wasn’t a case of if you were going to join up, but when’.

Bhíodh na cruinnithe earcaíochta ina gcíor thuathail uaireanta, agus dar leis an Connaught Tribune i nDeireadh Fómhair 1914, ba gheall le ‘guerrilla warfare on a small scale’ na troideanna ar an tsráid idir grúpaí beaga d’Óglaigh na hÉireann, a bhí i gcoinne Éire a bheith sa chogadh, agus a gcéilí comhraic as na hÓglaigh Náisiúnta, dream níos líonmhaire. Ag slógadh earcaíochta ar an bhFaiche Mhór i mí Iúil 1915, thosaigh Máirtín Mór McDonogh, an ceannaí is mó ar an mbaile, ag scigmhagadh faoi scata spailpíní a bhí ag fanacht le hobair a fháil: ‘I’ll hire you and I will give you more pay than you will get from the farmers. Why do ye not go? Perhaps ye were thinking that on the lands that ye were going to there would be no German bullets, well, ye will be in as much danger on the bogs from God’s lightening as on the battlefield from German bullets.’

I ndiaidh do John Redmond a thacaíocht a ghealladh do thaobh na Breataine sa chogadh i Meán Fómhair 1914, bhí cruinniú rúnda ag complacht Óglach an Choláiste agus, i ndiaidh dóibh vótáil i bhfabhar John Redmond, dhiúltaigh siad ainmneacha na n-oifigeach nua ná an méid a phléigh siad a scaoileadh leis na nuachtáin áitiúla. Bhí buíon beag poblachtánach i gcoinne an chogaidh i nGaillimh agus ba iad an tOllamh Ó Máille agus an tOllamh MacÉnrí is mó a luadh leis an gcáineadh poiblí ar obair John Redmond.

I ndiaidh scliúchas idir lucht tacaíochta Shinn Féin agus baill de Pháirtí Parlaiminteach na hÉireann i nDeireadh Fómhair 1914, scríobh Thomas Kenny, eagarthóir ar an Connacht Tribune, ‘Sinn Féin has been treated with generous tolerance in the city, it has grossly abused that tolerance… now the attitude is that tolerance has reached its limit, the puny plotters have only themselves to blame.’

Chaith Thomas Hynes breis is leathchéad bliain ag obair mar chúntóir/teicneoir saotharlainne i gColáiste na hOllscoile, Gaillimh. Mar bhall de Bhráithreachas Phoblacht na hÉireann (IRB)agus d’Óglaigh na hÉireann, rinne sé buamaí bréana i saotharlann cheimice an Choláiste agus úsáideadh iad seo go rialta ar na cruinnithe earcaíochta sa bhaile mór. Dúirt sé go ndearna siad a ndícheall deireadh a chur leis na cruinnithe earcaíochta ach go hiondúil buaileadh iad mar go raibh ochtó faoin gcéad de na daoine i gcoinne Shinn Féin, toisc go raibh a bhfir chéile nó a gclann mhac in Arm nó i gCabhlach Shasana.

I ndiaidh buamaí breana a úsáid ar chruinniú earcaíochta i Halla an Bhaile i nDeireadh Fómhair 1914, rinne an Galway Express cáineadh ar na ‘German Huns in Galway’. Chuir sé in leith gur chaith siad aigéad sulfarach (rud nach raibh fíor) agus d’áitigh:

A more infamously cowardly proceeding than that stated to have taken place has hardly been exceeded by the Huns in Belgium... The Huns are cultured, there is no claim to culture in Galway. Sulphuric acid is commonly thrown by jealous women who would blind and disfigure a rival in a love affair. For liberty loving men to squirt it at a platform of people exercising the common liberty of discussion is an example of the ‘liberty’ that ‘ourselves alone’ if left ‘alone’ would accord to free men.